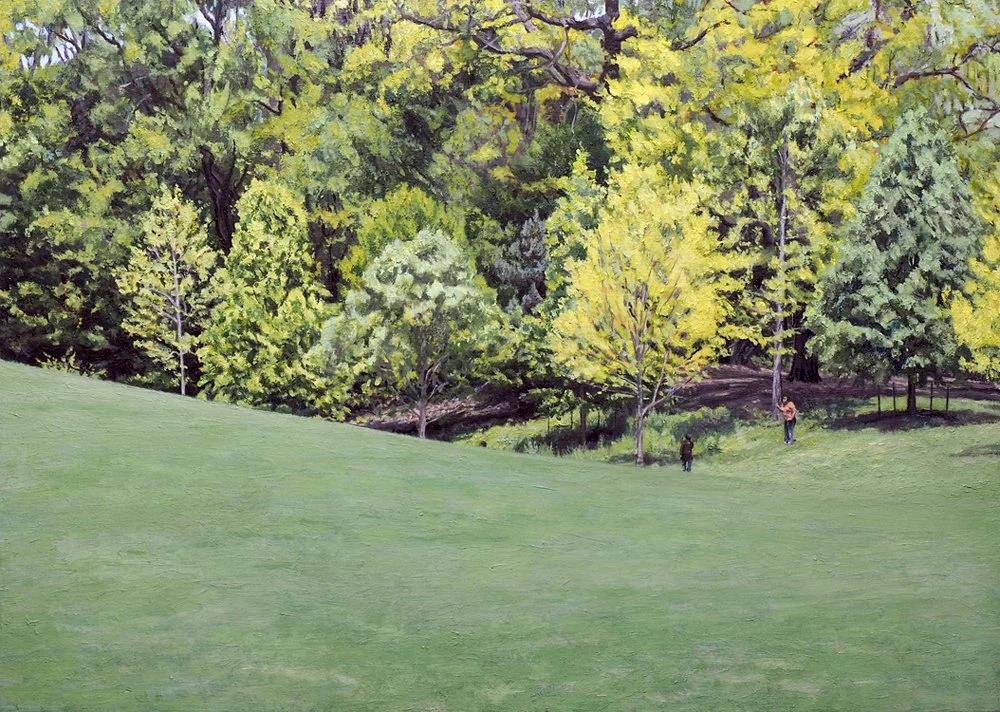

At Minneapolis' large

Lyndale market, on late summer weekends, you'll find lots of folks perusing, window shopping, often

eating some kind of corn, brat (said brot) or danish. There is a difference from the markets I have become accustomed to back in NYC, largely Brooklyn's Grand Army Plaza or the Union Square Greenmarket. Those markets have served as a kind of model and have skewed my experience of the markets here in Minnesota.

On the wooden table are paper trays, each carrying two or three tomatoes. I'll get to the trays in a minute, but let's fix on the sign. It says "Home Grown Tomatoes $5 each tray." For those regular to or familiar with Greenmarket might wonder if these folks are farmers or neighborhood gardeners. Home grown?

"Home Grown" to a Minnesotan means that this produce was grown locally, probably within 100 miles. You might think, "isn't that obvious, or isn't that required to be a part of the market?" Well no, here it is not. At the market you will find several

resellers -distributors of produce from bananas to corn grown by someone else and likely somewhere else in the world. Not to be kept in check by ideological purity, this market believes if you're out for home grown tomatoes you may also want to pick up your weekly supply of bananas. So it is that you see little placards, usually handwritten, stating that these tomatoes are grown by us farmers, locally. When you don't, whether it is or isn't, home grown remains in question.

Trays. I'm not sure why this has come to be the accepted presentation of produce at Minnesotan farmers' markets, but it is the norm for most markets. It serves to keep people from squeezing every tomato because one doesn't pick through the trays, or even the half pecks or bushels. You must buy the whole bucket.

At the crowded weekend markets there will be enough trays displayed on tables to give you a feeling of plenty, but that ordered plenty is nothing like the cornucopian dream overflowing tables under some of Grand Army's tents. That display of abundance offers such deep reassurance, it leaves you feeling rich and spending more, whereas the ordered compartmentalization of produce on Minnesota farm market tables leaves you feeling that you've received your share.

The scant baskets at small town farmers' markets presents like a Soviet dispensary. A single basket of tomatoes, two of potatoes, and three of pickling

cucumbers hardly seems worth the effort for the farmer or for us. All of which leads me to think of the nature of these markets, how they are, in broad generalization, an urban affair that caters to the whims and desires of an urban mind that requires such comfort as the perception of overabundance in the countryside. I am a bit conflicted on whether or not to indulge this fantasy or whether or not farmers should, yet I do enjoy its effect no less for being aware of it.

The Minnesota climate favors vegetables suited to three months of long day growth, little in the way of tree fruit, melons or any other long season, heat-loving produce. The staples are there: tomatoes, carrots, cucumbers, eggplant, bell peppers, etcetera, but the markets lack surprise and adventurous experiments. Are Minnesotan diets less adventurous? Do regional culinary traditions create limits?

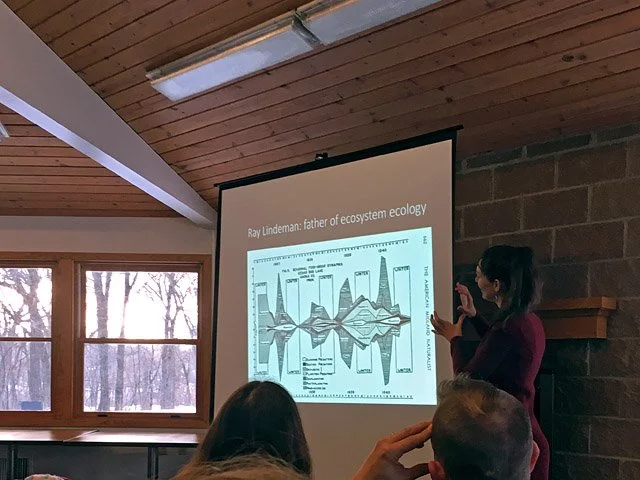

Fresh produce farming in Minnesota has largely shifted from a German/Norwegian/Polish to a Hmong enterprise. This demographic shift has brought most of any new variety to the market. In fact, any excitement in going to market lay in the good southeast Asian produce available. Are the neatly arranged baskets and nearly flawless produce a Hmong introduction?

Minnesota agriculture is a 20 billion dollar industry, but the majority of that is giant farm commodity production: corn, soy, barley, wheat, oats, sugar beets. The vast,

vast majority of farmers in Minnesota are white men of an average age of 56 operating on 25 million acres or nearly half of the state's land area. Of the tens of thousands of farmers, less than 500 identify as Asian American. At the Lyndale location of the Minneapolis Farmers' Market, I hazard the guess that half of the vendors are Asian American. This alone tells me we would have much less fresh, "home grown" produce available to us if these farmers weren't so enterprising.

Few of these market farmers are growing organic produce, however. It's not that people aren't buying it or that it won't be found in nearly every large grocery store. Yet, at the weekend farmers' market, I think I saw one farmer out of several dozen that claimed "natural" or "no pesticide." My guess is that certification is a long and costly process to the market farmers, but there is also a short growing season and weather hazards a plenty. The yield reductions of organic growing, alone, could turn a profit into a loss.

As of the 2012 census, there were seventy three thousand farms in Minnesota. Of that number, roughly seventeen thousand have sales of less than $1000. Of that same number, roughly ten thousand have sales over $500,000. The other farmers, all 56,000 of them, have sales somewhere between $1000 and $500,000. These are not profits or even salary, just receipts.

To keep yields up, market growers might require more labor and land, and I'm not convinced the traditional Minneapolis Farm Market customer is as willing to part with more cash for higher priced,

locally grown organic. Local farmers may have a hard time competing with the Cascadian Farms or Earthbound Farms you find at Whole Foods.

As much as I would like to enjoy the Minneapolis Farmers' Market or even our small local markets, I don't visit them often (I do go to a local apple grower for apples in season and our farm park for meats). Although our vegetable garden is small it provides us with three to four months of no pesticide produce and our local cooperative market fills in for much of the rest of the year. Sometimes I think of getting my garlic growing going again and I wonder whether or not I could find local customers willing to pay high prices for the crop. My experience has been that city-dwelling New Yorkers are excited by their

connoisseurship of the authentic, the obscure, the unusual in all things, even produce. I cannot say, yet, if that is true for the folks of Minneapolis -although if beer is any indication (better local beer here than anything I've had), it is possible.